Only 2% of the 2.75 million Ghanaians with mental health conditions are receiving care at medical facilities. That leaves hundreds of thousands of people without access to sanctioned treatments, and a great many who end up in chains.

read the full story

Only 2% of the 2.75 million Ghanaians with mental health conditions are receiving care at medical facilities. That leaves hundreds of thousands of people without access to sanctioned treatments, and a great many who end up in chains.

read the full story

All we can offer is the chain’: the scandal of Ghana’s shackled sick

Report: Tracy McVeigh Pictures: Robin Hammond / Witness Change for The Guardian

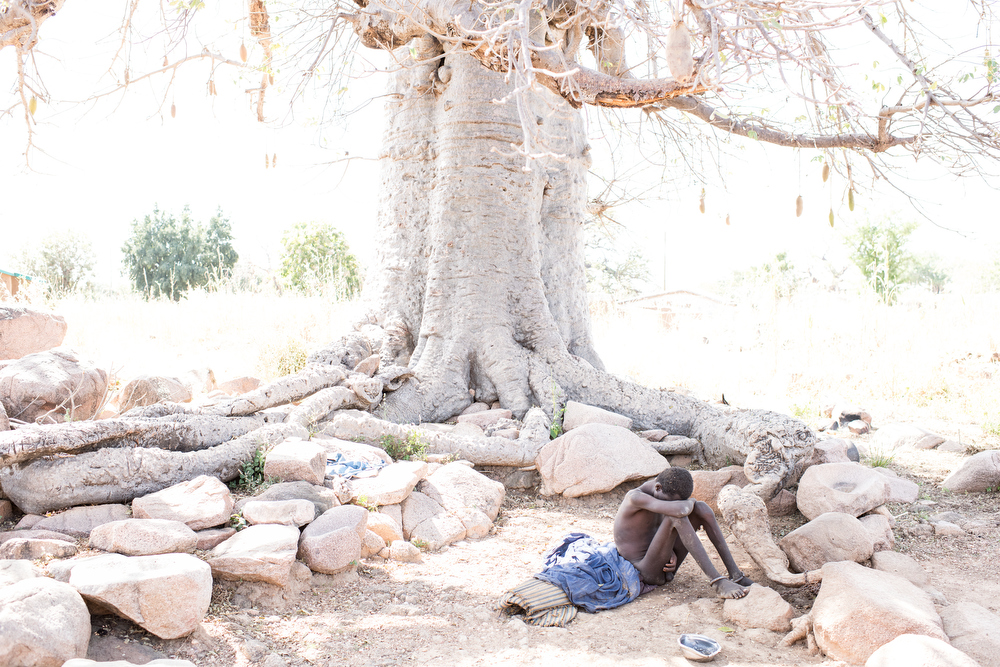

Under the baobab tree two goats are tethered to the great trunk by ropes. Baba Agunga, a man in his twenties, is held by chains. A bracelet shackle round each of his ankles leads to a chain rusted to the same tone as the Ghanaian mud and welded tight around a thick, solid tree root.

He sits naked on a cloth, hugging thin legs, his skin dusty dry and his eyes vacant. He has been there for three years says his mother, Aniah Agunga.

Through winter and summer, rainy seasons and drought, he has been tethered outside the main compound of the village of Zorko, northern Ghana, within sight of the family hut. His father who put on the chains has since died, his two sisters have married, moved away, had children. All the while Baba Agunga hasn’t moved beyond the earthen circle allowed by his four feet of chain.

His mother tries to explain why: “He was a good boy. He travelled down south and was fine, he was making bangles and selling them. He came home with friends who smoked marijuana. I don’t know if it was this weed that caused his sickness, but he became very aggressive. He had medication and he was better but then there was no drugs left,” she says.

“Then he tried to attack me with a cutlass. My husband ordered chains from the chain maker and this is how he has been for three years. The rain disturbs him and he is calmer in the dry season.

“I feed him when I can but there are days when there is no food. He always calls ‘mamma bring me food’.”

Her eyes water as Baba looks up to laugh into the sky. “I don’t know how old I am but it’s been 20 years since I heard the cries of my last child. I’m old,” she says. “So I worry what will happen to him when I am gone.”

There are no medical treatments available across this sprawling region for mental health or neurological conditions like dementia or epilepsy – which are lumped together. Across Ghana, a handful of community mental health nurses, three hospitals and 13 psychiatrists – most of them in the capital, Accra – serve a population of 30 million, and everyone seems to be convinced that psychotic and depressive illnesses are on the rise.

“Since we ran out of medication, the only thing on offer is the chain,” says Stephen Asante. A young and dedicated psychiatric nurse from Tamale, the capital of Ghana’s north, he works out of the city’s teaching hospital and has established his own charity Mental Health Advocacy Foundation – MHAF. He has persuaded local radio stations to give him airtime and he uses phone-ins to broaden awareness of psychiatric illness.

“Most people in the north do not understand the concept of mental illness,” he says. “So many do not know what to do and in most cases they abandon the person, or they take them to prayer camps. Maybe someone who has knowledge about mental health advises them to take the person to the hospital. But even there there is no medication.

“There have been no drugs sent to this area from the government for the whole of the year [in 2019]. Zero. Nothing,” says Asante.

Ghana is a country where spiritual and herbal healing traditions intertwine with one of the most successful universal healthcare insurance systems on the African continent. It has distinguished itself with a vaccination programme that compares well to other sub-Saharan countries and the government has made efforts to start to tackle the daunting medical professional skills shortage, a gap currently filled by faith healers, herbalists and con artists.

But, like in much of the rest of the world, mental illness is stigmatised and under-resourced. Prisons are inappropriately full of people with mental illnesses while medical facilities are empty of psychiatric understanding.

In west Africa fear and notions of evil spirits exacerbate the suffering of the sick, and the sight of people shackled to trees or stakes in the ground is not uncommon. It’s so prevalent that the practice supports an artisan industry – a “chain maker” can be found in every third or fourth village.

Asante is seeing a rise in young people with psychotic conditions and believes an increase in the abuse of drugs and alcohol, as well as the impact of poverty exacerbated by climate change, is creating downward spirals of need.

“The cannabis grown in Ghana is some of the strongest in the world. The abuse among the young guys and some young women who smoke it all day long, or take Tramadol or cocaine, is very bad. Mental health deteriorates like this,” says Asante.

Umama Belakoba’s condition is possibly caused by trauma. Chained by her ankle to a shea tree, her mother hovering nearby, she has two hollows in the earth which serve as her toilet and to hold drinking water. Her mother, also called Umama, says her constant chatter is incoherent. “My daughter has four children aged from eight to two. They miss her. Her husband went to jail for stealing yams and the madness came. So here she is getting calmer, improvements are small. She is not destroying her food bowl any more.”

This is the Nyinbonya prayer camp and pentecostal church of Pastor Isaiah Nchiroba, in Paga, near Ghana’s border with Burkina Faso, where Muslim and Christian prayer camps vie for custom.

The pastor has 150 patients, and about 20 are chained to trees around the grounds. He says his treatment can be “only prayer. I am an agent of peace.”

“I treat people for free, but they may compensate me if they want.”

He fasts too, and sometimes asks the mentally ill to fast with him. “Every day we have a Jerusalem cycle, seven times around the church in prayer.” Nchiroba says shackling is necessary for those who “can frighten people and even cause injury or make noise”.

John Yimbilbe has been chained to a tree at Nyinbonya for two years, his wife Elizabeth Kwamwe says. She stays with him, the pair sitting side by side, lowering a mosquito net down from the tree at night to cover them. The pastor feeds them every day, but they would like the chains removed.

Yimbilbe rattles his leg chains with one hand: “I hate them. I want to go home.” Kwamwe says he lost his job due to his “sadness” and would wander about at night so he was chained. “It comes into my mind sometimes to leave him, but he is my husband to take care of. There is love,’” she smiles.

Sara, whose last name wasn’t given, has a painful-looking swollen ankle where the bicycle chain that secures her to a tree digs in. “I have been sick after each of my three children were born,” she says. “I ran away from here when they first brought me because I wanted to see my baby. I don’t like being out here at night and to have to go to the toilet here.”

Asante thinks Sara has postnatal depression and he intervenes with the camp’s staff. “This is a nursing mother,” he tells the men. “I beg you she will not run away. Bring the baby for her.”

The debate gets heated and Asante decides to leave it for now and to return the next day.

“Respect for mental health officers in Ghana is very poor,” he says. “Some health professionals even tag us as ‘mad’. Anywhere I go, even at the hospital, my fellow professionals at different departments called me ‘mad nurse’. Since I started the radio show the response has been good. People who listened to me do come to the clinic or have been bringing their relatives for assessment and treatment.”

But the lack of drugs is, for him, the key issue.

“There is no difference in what the options are for a poor and a rich family,” he says. “They all should have the same access to mental health care under our healthcare system. But the difference is when there is no drugs at the psychiatric clinic and a family needs to buy the drug from the pharmacy. The poor family always has difficulty and at times they cannot afford at all, thereby they will abandon the patient.

Chaining and shackling have been with us for long. I think this practice has been in use before I was born. But the problem is not going away.”

Matthew Pipio works for Basic Needs Ghana, one of the only charities working in this field. It imports drugs, but it’s a trickle where the growing problem needs a flow, he says. “Virtually all the psychiatric cases in Ghana cannot afford drugs, even if they were available. Or some will get medication, but they return to the hospital and there is no more – this is a critical issue because it can make them not just relapse but become worse. It’s no good trying to tackle culture and beliefs if the political will is not there with resources.”

He thinks prayer camps can be useful because they present a human face, but “this dehumanising treatment of chaining should be stopped. Violence is used as an excuse, but through medication, people can be handled without chains and leaving them out in all weathers.”

“The rise in mental illness is a global problem and we have to tackle it or we will have terrible problems ahead,” he says.

Abaan Nyaaya, an Islamic healer who uses his grandfather’s remedies and refuses to resort to chains, has a queue of people at his clinic – a tarpaulin on posts. “The numbers are increasing too much, so that people do not know how to handle them,” he says.

He does not approve of restraining patients. “There are herbs to calm people. It is not right to chain. I tell people to take relatives home, they are not devils.”

A rise in numbers, alongside a rapid increase in suicides, is why the Edwuma Wo Woho Herbal and Spiritual Centre – whose sign reads: “We cure any kind of disease” – is expanding. King and his brother Herbert help run it for their mother Irene Dazie, a healer who learned her trade from her own mother.

Dazie is not keen to talk to journalists without being paid. Herbert explains that they need more money to finish the building work, which he says has stopped because of a bank collapse.

“We provide a great service and are using our own money to help thousands. But we get no money to support our work from NGOs or from the government. We work hard. We are giving them food and clothes and a shoulder to cry on and they pay nothing. But my mother has never contemplated giving up. We are seeing thousands now with mental health problems. Some are witches, some have drug problems or family problems. Sometimes people come from Niger, Togo, all over, because my mother’s reputation is very big.”

The centre is built around a courtyard with treatment rooms, waiting rooms and a place where great cooking pots bubble over open fires, full of strong-smelling herbal concoctions. In one dark, large, low-ceilinged room around 20 men sit around on the floor, many stripped to their underwear in the sweltering heat – each with their legs encased in shackles chained to one of the concrete posts.

Those who will talk complain that water is not available and that they have not consented to such treatment. King says it often takes six men to hold patients down to chain them, but that it is necessary to keep people safe and stop them running away or fighting. There have been stabbings, he says. “We need a fence here so we can release them from chains,” he says.

The brothers bring out patients to speak. “I would recommend this place,” says Jacqueline Kyeir-Baffour, 22, who was self-harming. “The stigma is not easy so when I was in chains it was because I was going to run. I was in chains for three weeks but I felt it was spiritually healing. I felt this was a safe place,” she says. “I had been feeling not well at all, very strange in myself. Mamma has given me advice about life, about connecting with friends.”

The World Health Organization estimates that only 2% of the 2.75 million Ghanaians suffering from mental disorders are receiving care at medical facilities, mostly on the southern coastal belt. That leaves hundreds of thousands of people without access to sanctioned treatments – a great many of whom seek help at spiritual camps operating without government oversight.

In Ghana, as elsewhere, the stigma of mental illness is a poison that mutates those contaminated, in the words of sociologist Erving Goffman, “from a whole and usual person into a tainted, discounted one”.

In Zorko, with the possessions of her entire life on view inside the tiny, round mud hut – pieces of worn fabric, a huddle of pots and utensils, a near-empty dirty-white rice bag, an empty catering-sized margarine tub – Aniah Agunga peers into her visitors’ faces to see if anyone has a miraculous solution for the pitiful scene under her baobab tree.

Stephen Asante promises to try. “That is a human being,” he says, walking back along the dry track pricked with sharp grasses. “This cannot go on.”