read the full story

read the full story

In the most traumatised place on earth, a search for peace

A Witness Change story with photos and text by Robin Hammond. This work was made in collaboration with Medecins Sans Frontieres and The Guardian.

One of life’s greatest misconceptions is a simple fable. That time is a healer. One year ago on the 25th of August “ethnic cleansing” perpetrated by the Myanmar military against the Rohingya sparked a massive refugee crisis. Nearly a million Rohingya – those who escaped the flames and executions – are now living in camps in Bangladesh. Many of them were raped, most saw loved ones killed, thousands arrived wounded. All are traumatized. Here, in this impoverished monsoon soaked corner of Bangladesh, is one of the most densely populated areas of PTSD affected and depressed people on earth.

Here, time has not healed.

Fleeing flames and bullets, the Rohingya had little time to gather their possessions. Crossing monsoon-swollen rivers and trekking through sucking mud, what they held onto tightly were their very young, their very old, their injured, and their religion.

The Rohingya are a Muslim minority in Buddhist Myanmar. Their religion and their distinct language cast them as foreigners in the eyes of their Buddhist countrymen. Decades of marginalisation and persecution have stipped them of much, but they would give up their faith for nothing.

In the Bangladesh refugee camp where hundreds of thousands of Rohingya live, mosques have been built. So have Islamic schools. On an empty white World Food Programme sack, 12-year-old Johura Begum sits reading the Qur’an in this bamboo-walled madrasa, obediently reciting verses in Arabic. She sits slightly apart from the other girls, who giggle covering their faces with their scarves when a camera is raised to take their picture. Johura doesn’t laugh with them. That kind of laughter is not part of her life. Not since she watched 14 of her 16 family members be killed.

Nightmares take her back to the execution of her parents and siblings. But her most regular dream is of eating a meal with her mother and sister in their Myanmar village.

What food do you like? “I don’t feel hungry.” Ever? “If I feel very hungry I have a little rice.” Why don’t you enjoy eating? “When I think of my parents I don’t feel good eating.” Do you think about them often? “Yes. I do. With every breath I take.”

“I do not feel peaceful,” Johura says.

“Mental illness” does not translate into the Rohingya language. Instead they talk about a peaceful state of mind to express wellbeing. Un-peaceful minds are troubled, depressed, anxious, traumatised.

The Rohingya have more reason than most not feel at peace.

The severity of the violence they have faced is difficult to comprehend. There have been many accounts of men being rounded up and killed. Women have been raped. Some women and children have been killed too.

Rohima Khatun’s story is typical. After encircling her village, the Myanmar military started burning houses. Through the smoke and heat strode the uniformed executioners and rapists. They went house to house and shot the men. Rohima saw her husband killed. The women were gathered in the village school. Rohima, five months pregnant, held her four-year-old to her chest, and her six-year-old to her side. The older of the two was screaming. A soldier marched forward, picked him up, and threw him into the burning flames of a house.

Then the raping began.

Somehow Rohima, in a state of shock, managed to slip through the smoke and into the jungle. She saved herself, her four-year-old, and her unborn child.

“Every single moment I remember this,” she says. “And I get emotional, because I lost my neighbour, my husband, my child, my relatives.”

While the physical wounds of the surviving Rohingya have healed, the psychological scars remain. Few have been left unscathed.

Refugee camps are what some organisations working in mental health call disabling environments. “It is really hard when they are living in the camp to be able to cope,” says Jodi Nelan, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) mental health activities manager. “So a lot of people find it difficult to move forward.”

Nelan heads a team trying to help people get back on their feet. “They can learn to put their lives back together,” she says. “They do that by relying on coping skills. We can help them.” A team of MSF counsellors has carried out 5,700 individual consultations and just under 12,000 group sessions.

In the most recent months MSF psychologist Shariful Islam has seen a shift, from symptoms indicating trauma to “depression, anxiety, hopelessness and domestic violence”.

“They say: ‘I don’t have any hope and most of the time the scenery comes to my mind, how they tortured me, and how they killed my mother, how they killed my very small child. And when I remember all of this I can’t keep control of myself and how I behave. Sometimes I beat my family member.’ We are noticing that this kind of patient is increasing significantly.”

Heightened aggression is associated with PTSD and some victims of violence are developing mental health issues that see them perpetrate abuse. When societies and the connections that bind them are ripped apart, piecing them back together rarely results in full harmony.

The situation differs for men and women. Women can still be carers and mothers, and run affairs inside the house. In this conservative culture, men are expected to be protectors and providers. Unable to work, and watching their families live off handouts, many feel useless – their role and identity taken from them.

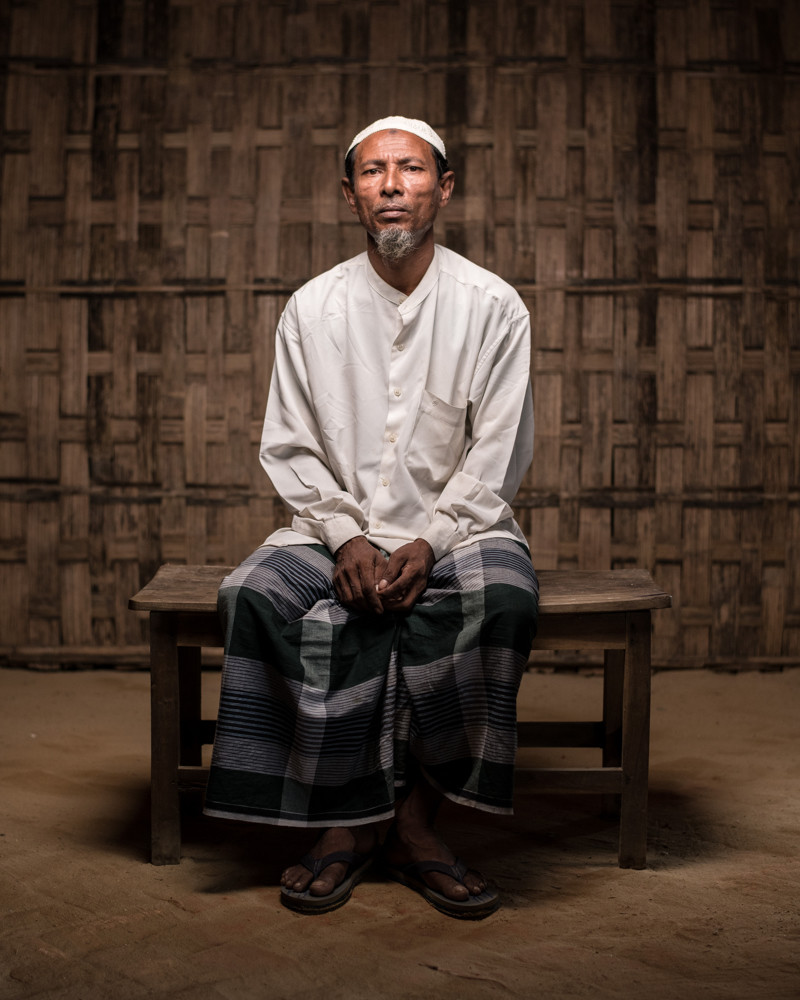

Abdul Hafez, 47, used to be a farmer but his life has been turned upside down. “I can’t provide the things that my women and children are looking for,” he says.

Losing his sense of self has added to the trauma he lives with. “I often remember what happened, I try not to be angry, sad, frustrated – I try to bury that pain and sleep more.”

The suffering here is immense, but walking through the camp, it is evident how much life there still is here. Children are born, couples get married, boys play football, girls apply makeup. The vegetable market is busy, the call to prayer reminds the devout to go to mosque, little children all over the camp chase foreigner aid workers (and journalists) shouting “bye bye, bye bye”, laughing like it’s the funniest thing ever. The resilience of humanity, the ability to find light and peace in even the darkest places, is on display.

Johura cannot see much light. She thinks a lot about the night her family was murdered, of falling into the river as she ran, of climbing up the muddy slope of the riverbank and finding her sister’s body, lying in the shallow grave she was made to dig before she was shot in the face. As Johura stood over the muddy hole, in shock and losing blood from a bullet wound to her hip, she collapsed.

The trip from there to Bangladesh, where she was carried by survivors from her village, was a blur of semi-consciousness. Fortune briefly shone on her during this nightmare. She shook awake just as they passed some boys – from the shoulder of the man carrying her she recognised her 10-year-old brother – her only surviving sibling.

And there is her light. The glimmer of hope in which she might find peace. Neither food, nor friends, nor playing, nor pretty dresses make her happy.

How about you brother – does your brother make you happy? “If my brother is happy, that can make me happy – in here, he is the only one who can.”