Roughly five million Japanese people currently live with dementia, by 2025 that number will be 7.3 million or one in five people 65 or older. 40% of these people live with family members, a financial and mental stress which many Japanese households can’t afford. But with Japan’s “Orange Plan”, education and community support (coupled with 22.5 billion yen) are making the country an example for others.

read the full story

Roughly five million Japanese people currently live with dementia, by 2025 that number will be 7.3 million or one in five people 65 or older. 40% of these people live with family members, a financial and mental stress which many Japanese households can’t afford. But with Japan’s “Orange Plan”, education and community support (coupled with 22.5 billion yen) are making the country an example for others.

read the full story

‘I still dream of my husband’: life with dementia in Japan

Pictures: Robin Hammond/Witness Change for The Guardian

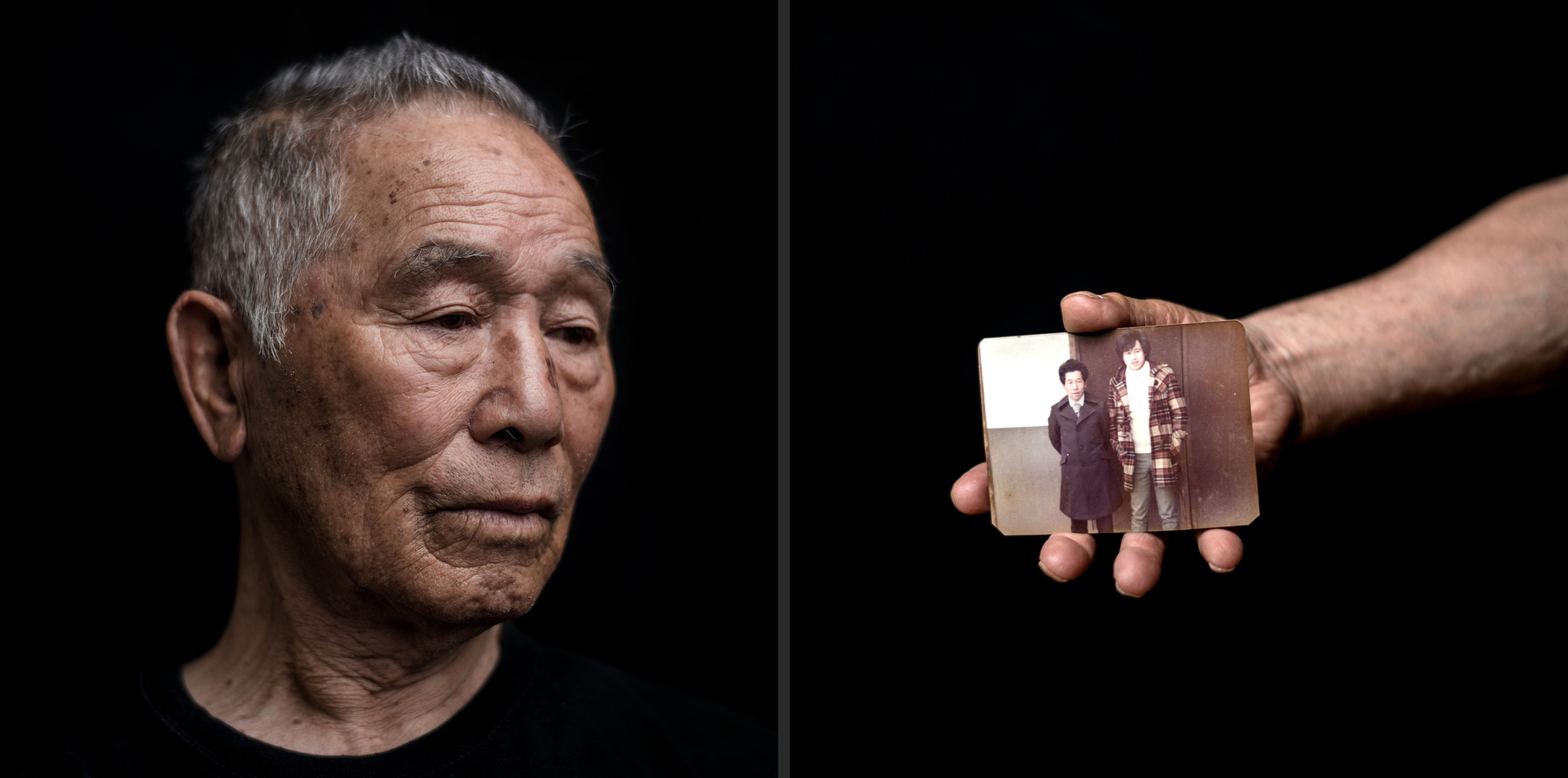

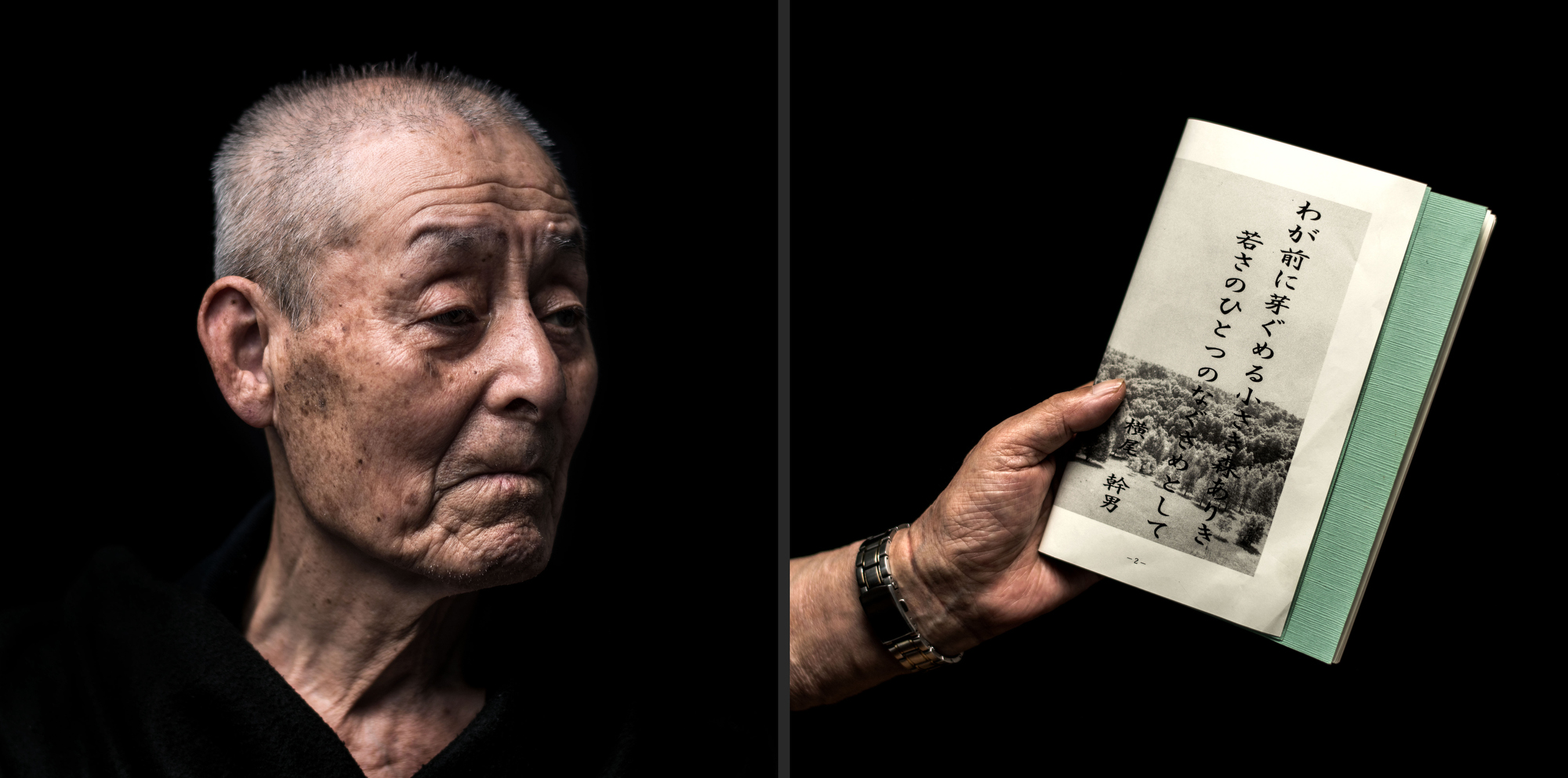

For the millions of Japanese people living with dementia, diagnosis is often the beginning of a journey into a life of seclusion.

When dementia is covered by the media, it is in the form of news about experimental therapies, or reports on the latest police campaign to encourage older people to surrender their driving licences.

The voices of people living with the condition – in ever rising numbers among an ageing population – are often missing from the public debate.

About 5 million Japanese people live with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, and 7.3 million – or one in five people aged 65 or over – will be affected by 2025, according to government estimates. Most live at home, cared for by relatives, 40% of whom warned they could not continue as caregivers due to stress and the impact on household finances, according to a 2015 survey.

There are signs of change, however. The city of Matsudo, east of Tokyo, won recognition at home and abroad for its groundbreaking approach to dementia several years before the national government released its “orange plan” – a 22.5bn yen (£160m) programme to hire more specialists, improve early diagnosis and expand community-based care – in 2015.

Matsudo made dementia a public health priority almost a decade ago, raising awareness of the condition among residents as well as businesses that regularly come into contact with older people. Several times a month, volunteer “dementia supporters” wearing bright orange bibs patrol neighbourhoods to distribute leaflets with information about dementia services and, occasionally, to help people in distress.

In the Sapporo and Eniwa areas of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island, the Megumi-no-ie and Komorebi-no-ie “group homes” cater for a total of 36 people with dementia.

Here, food and general care are provided, but residents are also encouraged to take a leading role in their daily routines, whether it be gardening, preparing meals, food shopping or cleaning. Some sell vegetables they have grown to give them a sense of financial independence.

Fumiko Ito, 69, ran a restaurant-bar with her husband for three decades. Ito, a resident of the care home in Eniwa, recalls that her husband, who died seven years ago, was married when they met. “I met him at my friends’ bar. I was drinking there and so was he … He was sitting behind me and he pushed me from behind and said: ‘Hi’. It was love at first sight. I was 18 or 19. He was 10 years older than me.”

“I often think about him and often dream about us together … he died from cancer,” Ito says. “He had a really difficult time coping with that. I sometimes think about that.”

Asked what makes her worry, she replies: “My health. I hope to stay fit for a long time … I hope to stay here with my friends and have a happy life here.” And what makes her happy? “I like food. I’m happiest when I’m sharing good food with friends.”

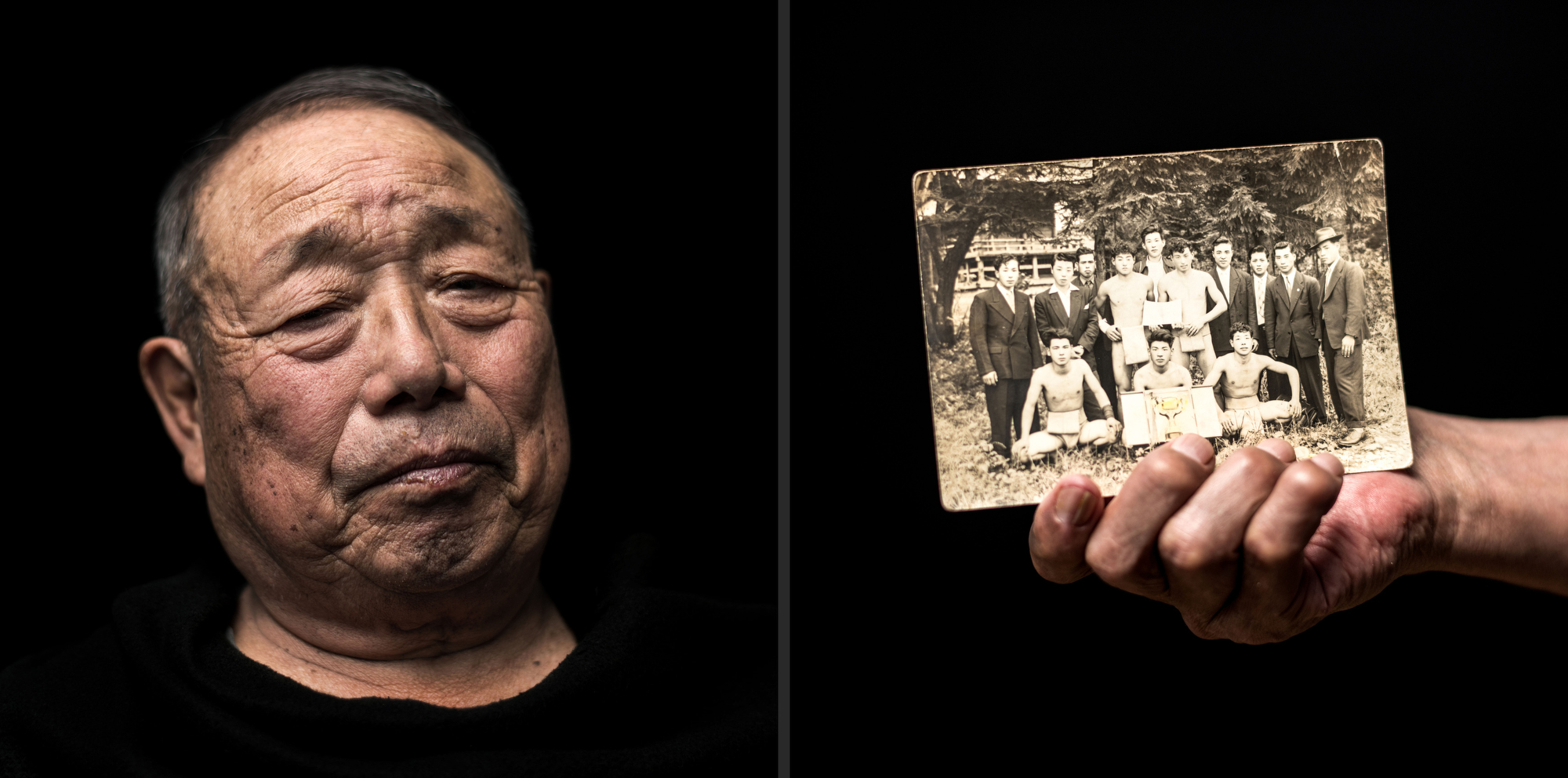

Ito’s fellow resident, 89 year-old Masanori Nohara, says he can be forgetful, but claims he “doesn’t give a damn” about the state of his health. “I sometimes forget things,” he says. “I know about dementia, but I don’t think I have it.” He recalls the joy he felt when he qualified as a joiner in his early 20s. “I became an apprentice when I was 18 and trained for four years. I was really happy when I qualified,” he says.

Being able to use the skills he learned as a young man can be a source of comfort. “I feel like I’m getting old when I’m tired … but if I’m still working I don’t feel like that. I can still work and I still have my tools, so if possible I still want to work as a joiner.

“I feel happy when I’m sharpening knives, because that’s what I used to do. When I sharpen other people’s knives they look very happy, because they cut better. And I’m happy because I can make other people happy. It also reminds me of my work.”

As a boy, Koichiro Furuta dreamed of becoming a professional sumo wrestler, but abandoned the idea due to family pressure to take over his father’s rice paddies.

Now 84 and living at the Eniwa facility, Furuta describes living with dementia as bearable. “I’m getting old so it’s natural to forget things, but I am OK – I don’t really have a problem with my memory.”

But he struggles to remember his age, and says he sometimes forgets the names of his family members, including his grandchildren. “There aren’t that many things I enjoy now,” he says. “I often cut the weeds in the garden, and because I used to be a farmer I take an interest in the weather.”

Furuta, who hasn’t farmed for at least a decade, adds: “I have no concerns right now, but I worry about being able to get enough water for my rice fields in the future.”

Shinichiro Fumoto, the manager of a housing service for the elderly in Chiba, near Tokyo, says interaction between the facility’s 41 residents and the local community is important for both groups.

“Closed elderly residencies are common but not good for the residents,” he says. “Sometimes people are against the building of care homes in their neighbourhood. So we want to make a space that is open and beneficial to the community. And by having an open space we can advocate for people with dementia.”

Local children come to the home’s snack shop and an adjoining shared space to study, play games and talk to residents. “More than 60% of residents see their mental and physical health improve within a very short time because they have freedom of choice and a role to play here, like working in the snack shop, gardening or cleaning. And some help other residents,” adds Fumoto.