In war and poverty, rates of mental illness climb. Instead of treatment there is often neglect or even abuse. This is the story of how bad it can get and a photographer’s faltering attempts to help.

read the full story

In war and poverty, rates of mental illness climb. Instead of treatment there is often neglect or even abuse. This is the story of how bad it can get and a photographer’s faltering attempts to help.

read the full story

Condemned – Mental health in African countries in crisis

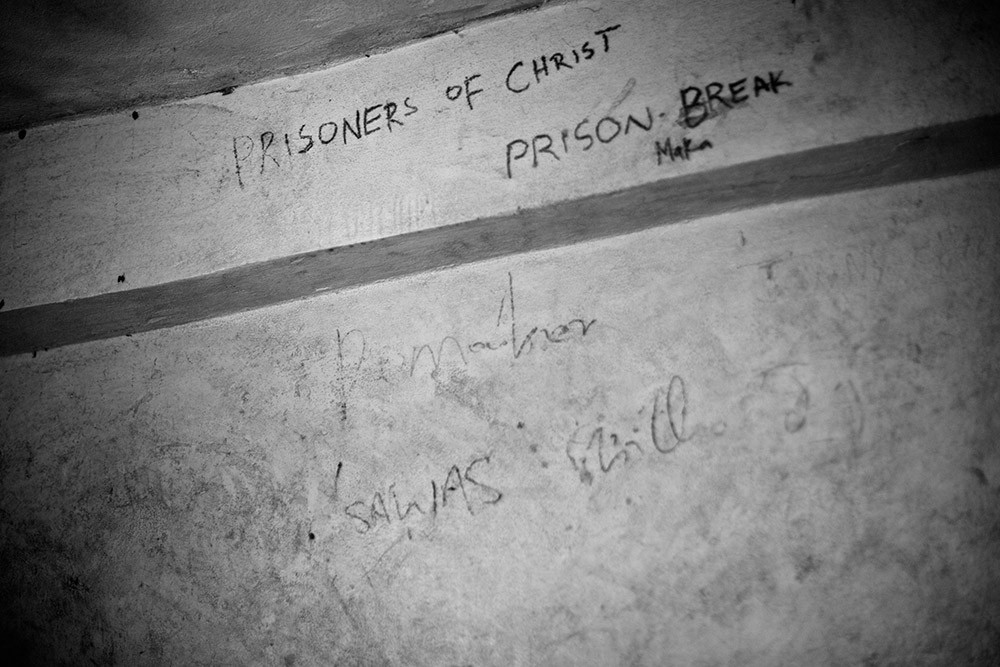

Condemned began in a dark and filthy prison cell in the Sudanese city of Juba. It started with a young man chained to a concrete floor. It began with a promise.

The photos were taken over a handful of days in January 2011, but they were 10 years in the making.

As a photography student in my hometown of Wellington, New Zealand in the early 2000s, I discovered photography that took me places I’d never go, that made me care about people I’d never meet. I fell in love with the idea of making beautiful, tragic, meaningful images that had the power to connect and in the words of the famous photojournalist W. Eugene Smith, “that might echo through the minds of men.”

I didn’t know then that the world of photojournalism was littered with idealistic dreams like mine.

Sure enough, ten years and thousands of pictures later, my romantic dream felt like a fantasy. In its final throes I grasped onto what little was left, for one last try at making photographs that meant something.

An assignment for The Sunday Times newspaper to cover South Sudan’s referendum for independence came in. My journalist buddy and I were to tell the story of a war-torn country about to be formally divided in two. It was big news. Journalists and photographers from around the world descended on the southern capital.

At this point in time, when I was so focused on making photographs that made a difference, it was hard to see how, amongst dozens of others taking similar pictures, I could contribute. I decided I needed to make a different kind of story.

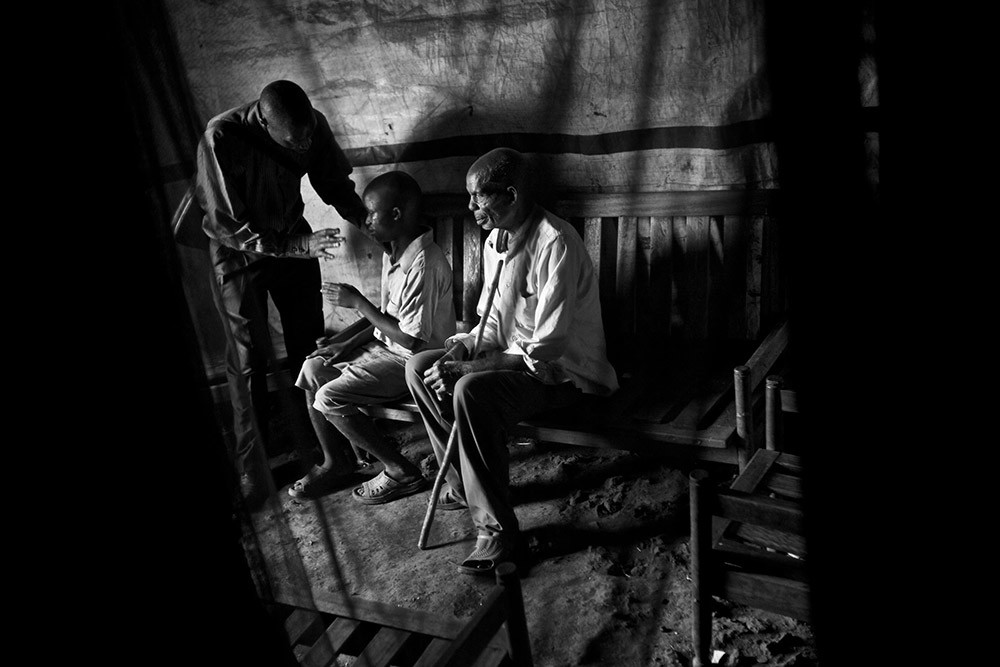

By the third day we were struggling to find a unique angle. Then, as we were driving around the city, we saw a young girl with a mental health condition begging on the side of the road. I asked the driver what happens to people with mental health conditions here. The country had suffered decades of war, poverty was rife, and given that barely a strip of tarmac road existed, I imagined there likely was no infrastructure to care for people with mental health issues. What was done for this vulnerable group I wondered? The driver’s reply: “We put them in prison.”

With that, the journey began.

At the time of writing this, eight years later, I’ve travelled thousands of miles through 17 countries documenting mental health stories. But as we drove towards the prison that day, I had no idea what I was beginning.

Unlike many of the places I would subsequently visit, gaining access to the prison in Juba took little effort. The South Sudanese were proud of their referendum and they wanted as many people to vote as possible, so they were allowing the prisoners to cast their ballot. They would be happy for us to see, they said. It also helped that our driver was the warden’s cousin. In this country of deep tribal bonds, blood relationships mattered.

We were guided through the main prison and the courtyard, where regular inmates spent their long days, to the back of the compound. As we got closer, the smell of raw sewage intensified. When we entered the last darkened cell in the group of buildings, the stench became unbearable.

I had strolled into a nightmare.

Our driver was right. Here they were.

I felt the butterflies of excitement – I had found our story. That was quickly suppressed by the urgency of documenting as much as I could as quickly as possible, the smell, and the gravity of the scene.

I had strolled into a nightmare.

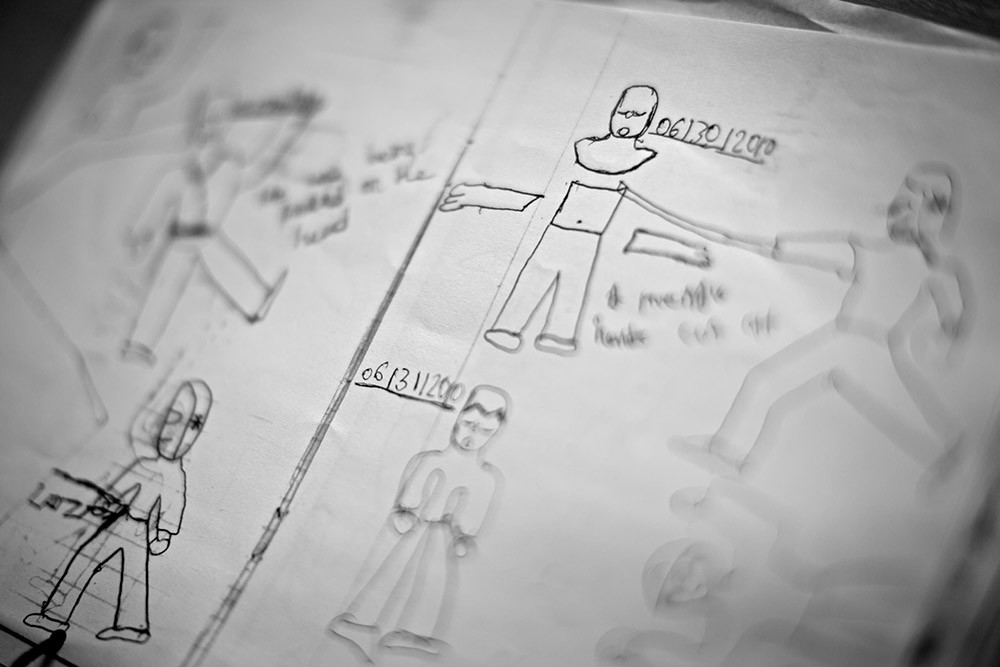

Some inmates were naked. Some were chained to the floor. Some spoke to themselves. Some were aggressive. Many didn’t speak at all, keeping to themselves and the dark corners of their cells. All were filthy. They were fed on the same floor where they defecated. The guard accompanying us could not tell me the mental health conditions of the people I was meeting. They were “mad,” that’s all.

I photographed quickly, anticipating to be told – as I had been many times before – that it was ‘enough, time to go’.

Most of the inmates acknowledged my presence and, I felt, accepted it in their own way. When those who didn’t expressed unease, I lowered the camera.

Amongst these poor souls in this hellish landscape, I gravitated towards one young man who neither looked at, nor spoke to me. He was completely naked except for the thick shackle at his ankle. He was lean, athletic. I thought he might have been 19 or 20 years old. He stood looking at the sky through the bars of the cell for a short time. Then he sat. As he reclined he took the form of a classical marble statue. But the shackle on his leg made me think of something else I had seen, or imagined seeing: images from the trans-Atlantic slave trade. I cannot point to the images my mind was referencing – only that here in this prison, with this young man, I saw beauty and I saw tragedy.

I had to take his picture, I thought. But as I was about to press the shutter, I caught myself. An internal struggle arose. I wasn’t sure if it was right.

I gravitated towards one young man who neither looked at, or spoke to me. He was completely naked except for the thick shackle at his ankle.

I recalled an interview with the renowned documentary photographer, and hero of mine, Eugene Richards, who had photographed neglected people with intellectual disabilities. He answered his critics, who felt his images might be invasive, by saying that he was there to “document a human rights abuse.” There, in this prison cell, his words reassured me. If that was justification enough for this pillar of photojournalism, then it was good enough for me.

But, I thought, by documenting this neglect and abuse, was I abusing his rights further? If this was me, my brother, my son, would I be okay with this image appearing on the front page of a newspaper?

I’ve heard picture editors argue that images that serve the greater good, may outweigh the rights of the individual (how else could one publish images of a starving child from Ethiopia, a wounded soldier in Vietnam, or an office worker plummeting to his death from a New York skyscraper?)

Could this image serve the greater good? Could the photographing of these people in this place actually help abused and neglected people with mental health issues?

These arguments ran through my mind in the few minutes I spent crouching in front of this young man with my camera poised to take his picture.

I settled the argument with a promise to myself.

I could take this image, but only if it really was used to benefit people like this young man, in difficult situations like this. If I could fulfill this promise, then I could live with the idea of taking of this photo.

If this was me, my brother, my son, would I be ok with this image appearing on the front page of a newspaper.

If I was going to take these pictures, I also had to take responsibility for having them make an impact

Of course the mission of my photography was to do good with my work. But over the previous 10 years, I’d always fallen back on something I heard another photojournalist with years more experience than myself say: “my job is to raise awareness, it’s the job of charities and campaigners to make change.” I decided there, that that was not going to be justification enough. If I was going to take these pictures, I also had to take responsibility for having them make an impact.

The work was published in The Sunday Times. The story spoke of this hopeful time in a new nation about to be born, and the costs its citizens had paid, including the mental health impact of decades of war – illustrated shockingly in the abuse of this country’s most vulnerable.

I had made strong and important images. I thought that when they were published, aid agencies and governments would rush into the prison to save these unfortunate souls. But that didn’t happen.

I contacted groups working on the ground in Juba. Surely they’d seen the story? Many had. What would they be doing? Nothing – I was told this was not a priority.

What support is there for people with mental health conditions in refugee camps, in failed states, in poor remote villages.

What I had encountered deeply moved me. Many others told me it moved them too. But that somehow was not translating into action on the ground.

Despite this initial failure, I received just enough encouragement to rekindle my faith in photojournalism as a force for change. I decided this is where I would try to have photography make a difference.

Beyond that, this trip to Sudan was a personal revelation. I had covered crises all over the African continent but had never thought about the mental health impacts of those disasters. Not only had I not thought about the trauma of people who lived through difficult times, but I had never considered what happens to the infrastructure of care when governments collapse and health professionals flee. What support is there for people with mental health conditions in refugee camps, in failed states, in poor remote villages?

Over the next two years I would find out.

I made a list of the sub-Saharan African countries I knew had faced particularly difficult times. Somalia was known to be the world’s most failed state. The Democratic Republic of Congo had been through wars which killed millions. Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya was the world’s largest home for displaced people. Northern Uganda had been through a horrifically brutal war. 10 years earlier, in Sierra Leone and Liberia, warlords had recruited child soldiers in bloody conflicts that had killed and mutilated thousands and compounded the country’s poverty. Nigeria was infamous for extreme levels of corruption and inequality.

The photographs I would take were evidence that South Sudan was, sadly, not an exception when it came to the neglect of people living with mental health issues.

The work won awards, was shown at photo festivals and published around the world. I collaborated with not-for-profit organizations and used it to campaign the United Nations to take mental health more seriously. I made a book of the work and sent it to influential people.

But that promise to make a change for people like the young man in Juba prison, did I fulfil it?

But that promise to make a change for people like the young man in Juba Prison, did I fulfill it?

It did make some difference. The work is regularly used by campaigners to illustrate the great need for mental health support in certain developing countries. And a major pharmaceutical company cited the work as instrumental in having it commit to greater involvement in the poorest countries on the African continent.

After the work from South Sudan was published, Handicap International, a French non governmental organization, started working in the prison in Juba. Three years later, 80 of the 88 people with mental health conditions had been rehomed.

What of that young shackled man? I don’t know. I went back to South Sudan but was not allowed into the prison – my work there was not received positively by the South Sudanese government.

Even if he is in a better place, it wasn’t just about him. Today, if you went to many of the places where I documented this crisis, the people who I photographed for “the greater good,” if they are still alive, will still be there – tied to trees, locked behind bars, hidden away in church basements.

They’re still there because the solutions are not easy.

The people who I photographed for “the greater good”, if they are still alive, will still be there – tied to trees, locked behind bars, hidden away in church basements.

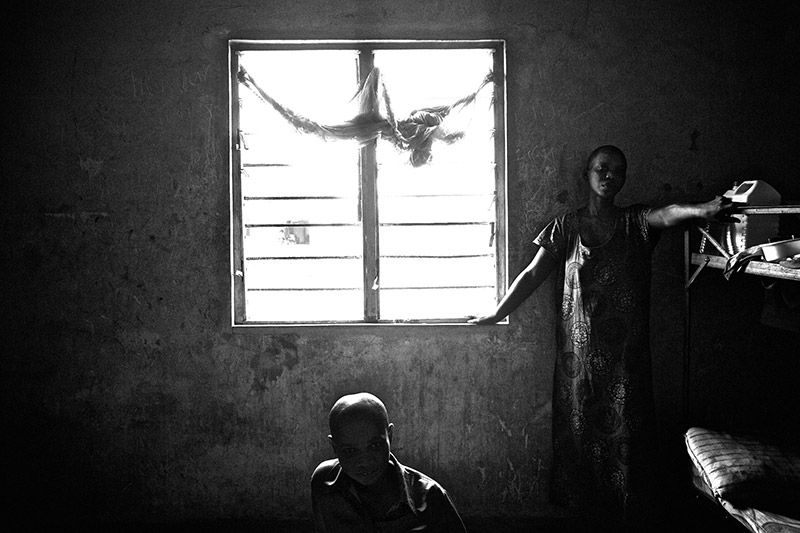

When there is no support, it can in fact be those closest to the individuals with mental health conditions who are the perpetrators of the abuse.

But we must be careful with blame. A woman in a refugee camp in Somalia taught me that we must think past our outrage and find compassion.

I came across her 13 year-old son tied by his ankle to a stick under a tarpaulin. I had been told that he had been tied like this for 10 years. My first reaction was anger. How could a mother do this to her own son?

The woman told me that it’s not about what she herself wants. She has four other children. Her choice is this: untie her son and care for him, and her other children will starve. Or she can tie him up and feed them all.

When a mother has no support, what does she do? Could tying her own child in fact be an act of love?

But we must be careful with blame. A woman in a refugee camp in Somalia taught me that we must think past our outrage and find compassion.

When a mother has no support, what does she do? Could tying her own child in fact be an act of love?

I saw there in that dusty desperate place that it is not as simple as breaking chains and unlocking prison doors. For that to happen, an entire system of care must be created that includes health care professionals, physical infrastructure, medicine, and support for relatives caring for family members with mental health issues.

That’s a big task when you consider that 90% of those living with mental health issues in developing countries, according to the World Health Organisation, receive no care at all.

Given the scale of the problem, maybe the promise I had made to myself in that prison cell in 2011 was never going to be fulfilled. And maybe it’s naive to think that storytelling can be part of the solution.

I don’t know.

The only conclusion I’ve come to is this: while there is no guarantee that my work will make the profound change that is needed, I know for sure that there will be absolutely no change if nobody tries.

So I’m for trying. That’s a promise I can keep.