read the full story

read the full story

After Fleeing War, Refugee Children Face Lasting Psychological Trauma

A Witness Change story by Robin Hammond made in collaboration with Médecins Sans Frontières and National Geographic

Text by Nina Strochlic for National Geographic

In the fall of 2015, Essam Daod was standing on the beach in Lesbos, Greece, when a crowded rubber dinghy packed with refugees landed ashore. Among them was an inconsolable five-year-old Syrian boy named Omar. Daod took him from his mother and pointed at the police helicopter circling overhead: “It’s come to photograph you with big cameras because only the great and the powerful heroes like you can cross the sea!” Omar stopped crying. “Am I a hero?” he asked in Arabic. Assured he was, the boy agreed to show the stranger the boat he arrived in: “I will show you where I sat and how I stopped the waves with my hands, and how I protected everyone,” he boasted.

In that moment Daod, a Palestinian child psychiatrist, realized there was a way to reshape trauma as it happened. Soon after, his mental health organization, Humanity Crew, launched the “Heroes Project” to train rescue volunteers and the Greek coast guard to rewrite the memories of the dangerous journey.

Last year, a Syrian-American medical organization announced that the severity of PTSD suffered by Syrian children surpassed the clinical definition and should be renamed “human devastation syndrome.” Mental health care for refugees is an invisible crisis that has remained on the backburner for NGOs and the international community. With little funding for treatment, the 1.5 million refugees who’ve arrived to Europe by sea since 2015 are largely left to grapple with psychological scars on their own.

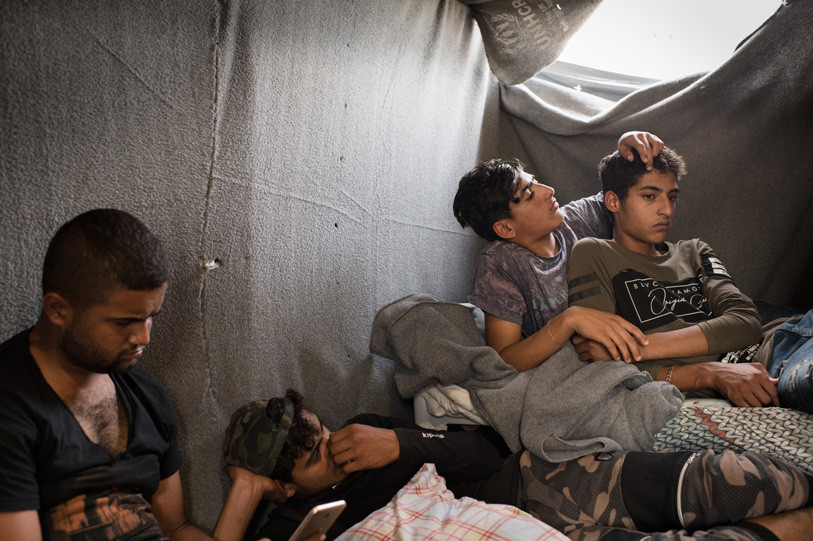

In Lesbos, 8,000 refugees are trapped after a deal between Europe and Turkey cut off their route into the mainline in 2016. Since then, living conditions and prospects for a life in Europe have deteriorated. The largest camp, Moria, is at double capacity, and some inhabitants having been there for years. A sense of hopelessness and unending detention has driven some to the brink—in May, one refugee set himself on fire outside an asylum office in the camp.

“People believe that once they become a refugee the struggle is over, but in fact the struggle is just beginning,” says Samantha Nutt, founder of War Child, an organization that provides education and psychological care for children in conflict zones across the world. “The risks they face escalate once they become a refugee.”

The scene of a rescue is chaotic: When volunteer rescue crews pull up to a boat, it can spark a panic. The dehydrated, sunbaked passengers shout, cry, and sometimes jump into the open ocean, terrified they’re about to be sent home. Those who came by sea—especially the children—will harbor a fear of the ocean for years to come.

When stunned refugees were pulled on board by crew members trained by Humanity Crew, they would congratulate the children for saving their families, ask for their autographs and take photos. After 15 minutes, the kids would transform. They’d talk confidently about how they’d saved the day. Later, when they settled into a camp in the island of Lesbos, stories and songs would be circulated about their bravery.

“Children’s brains have high elasticity,” says Daod. “If you do the right intervention as the trauma is happening, it allows you to transform a traumatic experience into an empowering one.”

In 2015, as thousands of refugees were arriving by boat each day, Daod traveled to Lesbos as a volunteer doctor. Later, back home in Israel, he started having nightmares. He was haunted by a child he’d dragged from the water and resuscitated. “Ok I rescued him, I did successful CPR—what else?” thought Daod. “He will be traumatized all his life. If I’m not going to give him the support for his mental health I shouldn’t give him the support for his life.”

To fill the vast, unaddressed need for psychological care he co-founded Humanity Crew. The small team took a new approach: rather than treating psychological trauma as a side effect of displacement, they considered it as—if not more—important as blankets and food. “First aid cannot be just for the body, but also has to be for the mind and the soul.” Daod says.

At sea, they taught rescuers how to reshape the narrative of traumatic events as they happened. Later they began addressing each of the four stages of trauma that every refugee goes through: leaving home, moving into a transit center or camp, seeking asylum, and being resettled in a new country.

In foreign countries, refugees, particularly minors, encounter a litany of new dangers. With humanitarian needs underfunded—the UN refugee agency is $1.5 billion short of its budget this year—many strike out from ill-equipped and dangerous camps in search of work. There are some 22,500 refugee children in Greece, and only half are in school, according to UNICEF. In most countries, it’s illegal for refugees to get hired in the formal sector, so they take informal jobs—begging, sex work, under-the-table labor.

While awareness about mental health issues among refugees has increased, it remains underfunded and under-addressed. “We need to define emergency human assistance much more broadly and look not just at the physical risks but the psychological risks as well,” says War Child’s Nutt. “There’s a perception that the psychological interventions are ‘soft’ compared to ‘harder’ ones, like how many blankets you hand out and tents you put up.”

In Greece, Daod says the mental health projects that do exist aren’t prioritized—often they’re staffed by people who don’t speak Arabic or understand trauma within the appropriate cultural context. One damaging trend is short-term volunteers who form deep attachments with children and then leave. Unqualified volunteers wouldn’t be deployed to counsel survivors in the aftermath of a school shooting in the U.S., says Daod, and the same should apply to survivors of war in a refugee camp.

Addressing these issues as early as possible is the most efficient step, but short-sightedness will pave the way for a lost generation. Daod has dark predictions for what will happen if the mental health crisis among refugee youth remains untreated. “Terrorism doesn’t recruit people—it fills gaps and mental health is a huge gap,” he says. “[Extremists] will come and give them meaning when they’re sitting in camps for years in the slums of Athens.”

Whatever the future consequences, those seeking a new life in Europe have seen the darkest side of humanity and are now left in limbo with no way to process it. After war, they have no “normal” to return to. “This idea you can get people back to normal is a mythology,” says Nutt. “What you can do is help people cope but it requires long-term thinking and resources. Unfortunately, for most governments the thinking is very short term and people fall further and further behind.”