Dementia kills more people than any other disease in England & Wales. In 2017 it affected 50 million people globally. These statistics are our parents and grandparents or soon, you and me. With no cure in sight, we have to consider how to live with it.

read the full story

Dementia kills more people than any other disease in England & Wales. In 2017 it affected 50 million people globally. These statistics are our parents and grandparents or soon, you and me. With no cure in sight, we have to consider how to live with it.

read the full story

‘Eventually I knew she was no longer safe alone’: how do we care for family with dementia?

She grips my hand and tows me behind her around the small courtyard garden, past the pretend bus stop and the red phone box with no dialling tone, down an alleyway of gravel that leads to a wooden gate. “Here,” she says. “It may be locked.”

It is, of course, securely padlocked. It’s hidden away but still Mum has found it. I take her by the arm. “It’s OK. We can get out the other way,” I say, leading her inside, through the chintzy cafe where no money is exchanged, to the lift. I bleep my electronic visitor’s pass. The doors to the outside world open for us. Mum walks through them, asking no questions, and admires the flowerbeds.

Even though she cannot remember what happened 10 minutes ago or when she last ate, even though this once immaculate lady, left to herself, would head for the street in a petticoat and one earring (“But it doesn’t matter, does it,” she said when I mentioned it), in spite of the holes in her mind that dementia has torn, the desire to go out appears hardwired. She found that gate, and then she remembered where she had found it.

Earlier I watched as Jean, Mum’s neighbour in the dementia home, walked up and down the corridor between her room and the communal area, tall and thin in her plaid skirt and jumper, the usual copy of the Times under her arm and anxiety on her face. Up and down. Back and forth. “Has my mother come?” she asks the carers. “No, I’m afraid your family aren’t visiting today,” is the answer. Her mother died years ago. They sit her down, suggest television or a game, and she is instantly on her feet, asking the same question again.

Dementia is the scourge of our age. We have become so good at patching people up bodily that for many, it is the mind that goes; dementia now kills more people than any other disease in England and Wales, accounting for 12.8% of deaths last year. In 2017 it affected an estimated 50 million people globally, with nearly a million in the UK; the numbers are expected to double every 20 years. David Cameron launched a research push for a cure in 2012, but one drug trial after another has collapsed, casting doubt on fundamental assumptions about what happens in the deteriorating brain. The central approach – targeting the buildup of amyloid plaques – appears to be going nowhere much.

Meanwhile, less attention is being paid to how we care for those whose minds are irretrievably unravelling, to where and how they should live. Most people in care homes – 70% – now have dementia. It may be best for many to stay at home as long as possible – but that means 24-hour care. The distinction between day and night can disappear. One of the first warning signs my three sisters and I had came when Mum started annoying the neighbours in her block of flats, pressing doorbells to be let back in at 5am.

Then there were the parcels. I drove her home one day, to find a large brown box outside the door. “Oh no,” she said, in genuine distress. “Not another one.” It contained what she and I would both have called quack remedies for ageing: potions and pills, and a Christmas cracker trinket of a bracelet. Inside was an invoice, paid on her credit card, for over £100. She had not ordered or paid for it, she insisted. And there were others. She had a cupboard full of expensive soaps and knick-knacks – a “sound amplifier” for £30 (there is nothing wrong with her hearing), a “cabbage detox” for £20. It had all been sent by two companies at the same address in France. I was livid. How dare they take advantage of her? But I now think she started it, sending off magazine coupons for hand lotion, though I know they got her to order more junk thereafter.

It’s odd how the signals are there, but you don’t see them. The flat smelling of burnt toast. I bought a new toaster. Her empty purse when she went out for coffee with friends. They paid. Her frequent trips in person to the bank. It didn’t occur to me that she no longer knew her pin number. The huge bills she was running up for newspaper delivery. The shopkeeper kindly said nothing. The frightening times I called in the evening, when it was dark, and there was no reply. Finally she would answer, out of breath. She had taken the wrong bus. One time she said a nice man had driven her home.

Eventually my sisters and I understood she was no longer safe alone. She resisted any suggestion that she had a problem. “I haven’t got that dementia,” she told me, sternly. But she agreed her memory was playing up. I used that to trick her into a GP appointment and referral to the memory clinic, where she was diagnosed, although no help was offered. We bullied her into twice-daily visits from a carer, who would sometimes arrive to find Mum missing. At Christmas at our house, she caught a virus and ended up in hospital, wandering the corridors at night. Staff refused to let her home without full-time care.

Mum hated losing her independence, the same way she had fought us when we “borrowed” her car a couple of years earlier and did not return it. I asked the carers to let her go – but follow her. At the home, where we moved her a year later because of her night wandering, and to be closer to my sisters, only the corridor and patio garden are open to her. She is not deceived, though she can no longer tell you what’s wrong. She is a “sundowner”: after tea, she will walk and walk, up and down the corridor. The challenges of caring for people like her in the way she would want, if she were able to explain it, are great.

There may be another answer. In a suburb of Amsterdam, Jannette Spiering sits at a cafe table in the sunshine, while women like Mum and Jean wander past. Spiering is the founder of the Hogeweyk, a dementia village whose fame has travelled the world. She used to help run a conventional care home on the site, which was torn down, and believed she could do better.

“We can try to come as close to normality as possible within the restrictions people with dementia have,” she explains. “These are mostly that they can’t make their own daily structure, and they don’t know when to eat, how to cook, how to dress, how to communicate. If they choose to go outside on a day like this, that’s not for us to decide. That’s why the front door of every house is open. We have to take care, if it’s cold, that people put a jacket on and that their shoelaces are tied so they won’t fall over them.

“Of course when people move in, they want to leave. I think I would, too, if I were locked up. But what I think is so lovely is you can go outside without someone watching or walking with you.”

“We can try to come as close to normality as possible within the restrictions people with dementia have.”

This is not a village in the traditional English sense. The houses, restaurant and a small theatre form the Hogeweyk’s perimeter wall. Look up and you see it is sandwiched between blocks of social housing flats. But there is space and sky. There are little gardens and a pond with statues of herons – and a real one that takes off as I walk by. The 23 houses, each for six or seven people, are different and separate, but joined as they might be on a terraced street. Outside are shady courtyards with wooden tables and chairs, flower tubs and trees.

The Boulevard looks like a town street, but behind the shop fronts are clubs. There’s the Mozart room, where classical music lovers meet. There’s a painting and baking club, which Mum would enjoy, along with any sort of singing. She croons with Frank Sinatra and bops gently to Rock Around The Clock, given the chance. At the Hogeweyk, families sign up their relatives for the clubs that will suit them, though too many activities can exhaust people, Spiering says.

In the square, cafe tables are set beside a fountain. Off it is an arcade, with a waiter-service restaurant and a supermarket where the carers shop for each house. If residents wander out with a packet of cereal or a bottle of juice, it can be returned or paid for later. And there is a pub: there is no reason why people with dementia shouldn’t enjoy a drink, although one daughter was scandalised that her non-drinking mother developed something of an advocaat habit. “She blamed us, but her mother just liked going there, attracted by the music or whatever,” Spiering says. People can change for better or worse; some start to use bad language; inhibitions disappear.

The Hogeweyk has its wanderers. A woman with Jean’s tense face walks the village paths stiffly and finally passes through sliding doors into the reception area, ignoring the notice that says “Sorry, we’re closed”. Behind their glass screen, the staff watch. She gets halfway to the double doors on to the street, which will not open unless the receptionists press their button, stops abruptly as if she has remembered something, turns around and walks back into the village. One of more than 100 unpaid volunteers intercepts and takes her for a coffee, to distract her. “There is still some part of her mind that recognises this is not her home and she can’t accept it. I think it is very sad,” Spiering says. Some residents walk all day long, so there are distractions to encourage rest: a large TV screen with seats in the arcade, and cafe staff instructed to invite wanderers in for a drink.

There is an element of the gilded cage of the 60s TV series The Prisoner, or The Truman Show, but while residents can’t get out, the outside world is invited in. Young mothers and toddlers meet here weekly. Locals use the restaurant and go to the theatre.

The Hogeweyk is not for the mildly ill. Everyone here has late-stage dementia. The average stay is 2.2 years, but some people die within a few weeks. Only three out of 169 residents are in bed all day, Spiering says, and these three are not segregated. “We put them in the living room with their bed, because they can still smell and hear what is going on and be part of it.” There is no sign of the agitation or aggression that often signals distress in people with dementia, no howls of anguish through an upstairs window.

Instead of severity of disease, as in the UK, the Hogeweyk allots residents to houses according to “lifestyle”. It’s not a class thing, Spiering says, nor anything to do with race: it’s about familiarity with your surroundings. The families choose which lifestyle is the best match. There are seven – urban, artisan, Indonesian, homey, Goois [a wealthy area near Amsterdam which once had its own dialect], cultural and Christian. The urban houses are home to former city dwellers; the artisan houses to people who had a trade or craft. The homey houses are for people, like my mum, who were homemakers; those who loved theatre and cinema are in the cultural houses. The decor and food will be typical of those communities. Some will prefer meat and potatoes; others are mostly vegetarian. The music is folk in some houses but classical in others; the newspaper on the table will be a tabloid or broadsheet.

Such segregation has its critics, but Spiering argues it is just what we all do for ourselves. We buy into certain lifestyles, or move to be part of a community we feel comfortable in. It doesn’t mean people won’t mix at the bingo group.

There may be an element of fantasy, but it is no more than in more traditional dementia homes – such as my mother’s, where people like Jean walk an endless loop of corridors decorated to look like a high street, with Singer sewing machines in alcoves and pictures of the Coronation to recall an epoch that is more vivid in the brain than the recent past. Reality is a tricky concept when it comes to dementia care, as Spiering points out. Some people want to go home, or wait for a visit from their long-dead partner. “We try to distract people, or we go along with them. We say, ‘Is it OK if we go for lunch first?’ You can say it’s a lie or you can say it’s not telling the whole truth.”

Dementia used to be dismissed as normal memory loss, a side-effect of ageing. People tended to die of other causes, much younger, so it was less understood. When German psychiatrists Alois Alzheimer and Emil Kraepelin classified it as a disease in the early 20th century, they focused on younger patients. The deterioration of the brain in old age was still regarded as an inevitability.

But by the mid-50s, US hospitals began to be overwhelmed by elderly dementia patients. Psychiatrists started to frame it as a psychosocial problem, finding that people from some backgrounds, with the same brain changes, did better than others. There were calls for programmes of activities to keep ageing minds stimulated. After Medicare, the US healthcare programme for the over-65s, was founded, people started to live even longer lives – and dementia soared. By 1980, everybody had heard of Alzheimer’s disease. Funds have been poured into research, mostly to find a pill to reverse it, without success.

Patients like my mum, who get a diagnosis, are prescribed a single drug, supposed to help slow the disease, and sent home. There is nothing more the NHS can do, or afford. Age UK and Alzheimer’s charities offer helpful advice, but you have to seek it out.

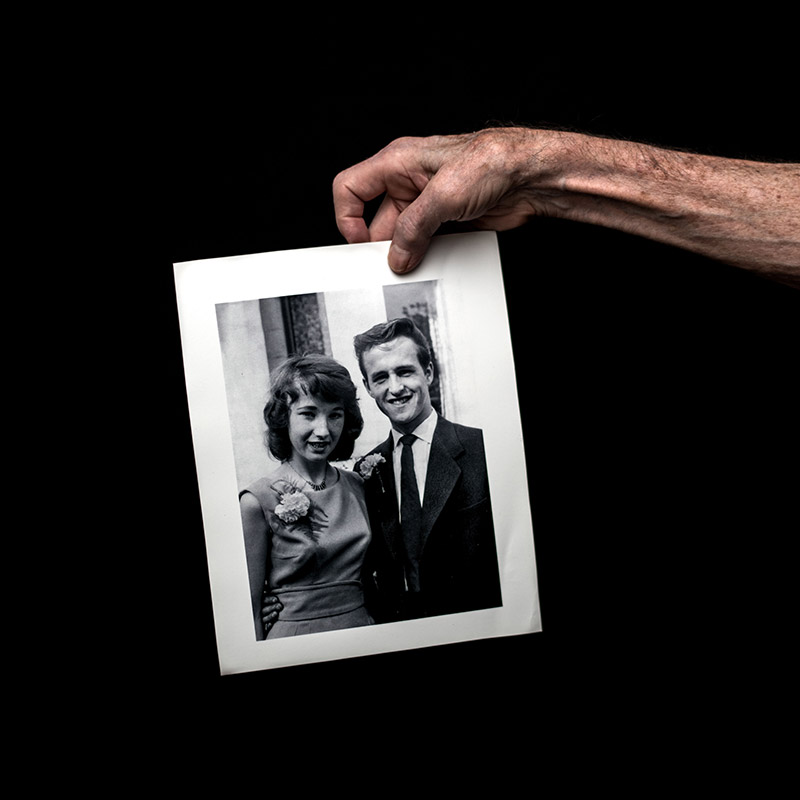

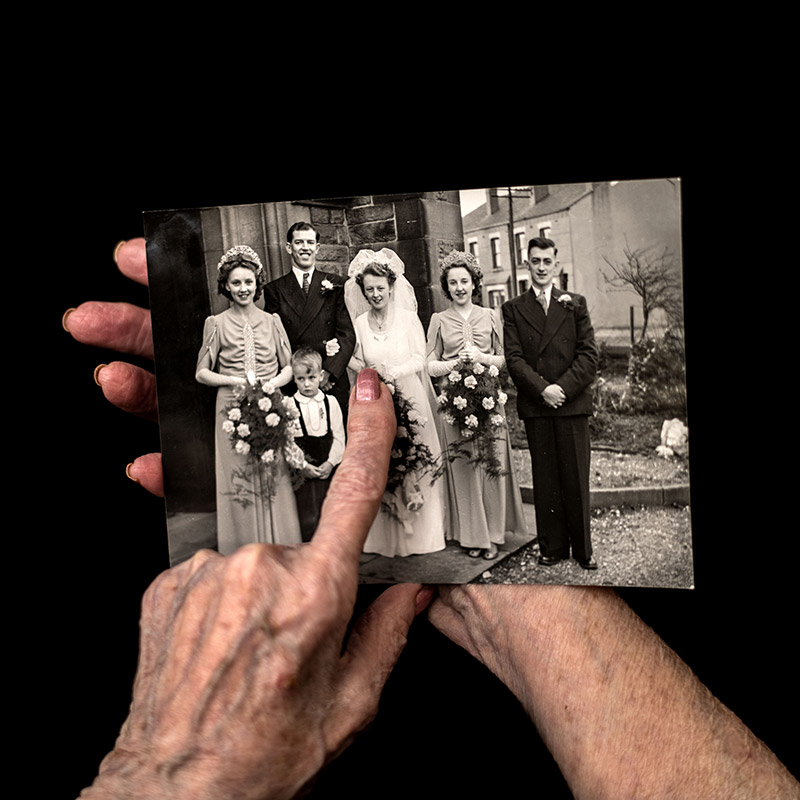

A third of people with dementia are in care homes, which seek to calm and stimulate residents whose memory of the recent past goes first. The walls are lined with photographs of Charlie Chaplin, Ava Gardner, the Queen as a girl. There are wartime singalongs. Living in the past is fine, as are white lies. We take Mum out for ice-cream and cakes at a garden centre, where last time she was overcome by the beauty of the flowers. “I can’t believe it,” she kept saying. We stay in the present moment and talk about the mackerel sky and the planes she thinks are birds. We never talk about dementia.

The truth used to be served up cold. “Reality orientation” was developed in the late 50s, on the basis that exercising the memory would keep it functioning better for longer. Patients were trained to know the name of the place they were in, what month it was, who the prime minister was – but it was confrontational and insensitive. If people knew that it was Thursday and that they were widowed, it didn’t make them happier.

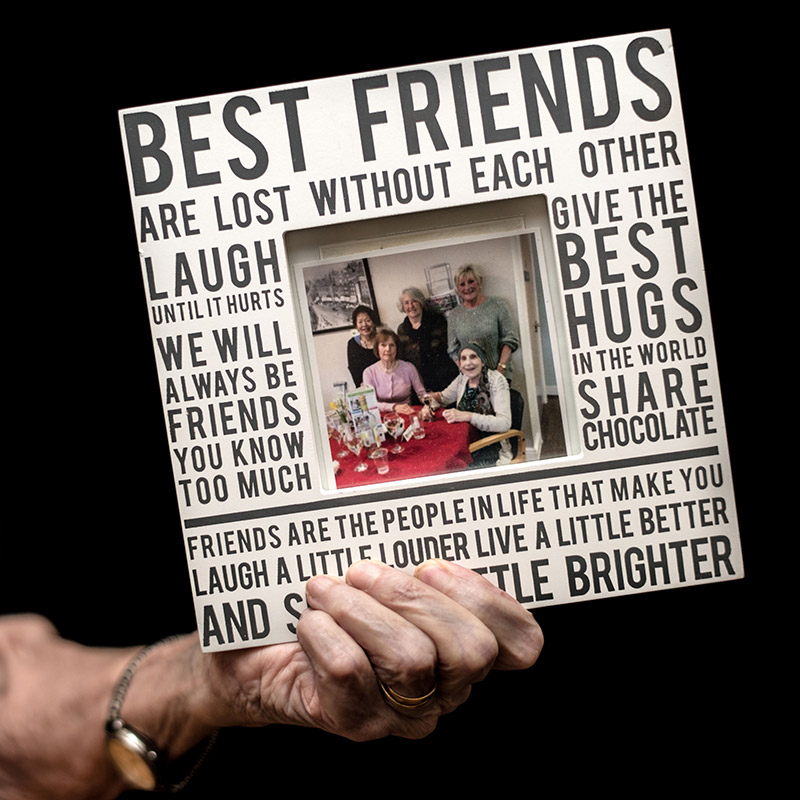

Instead the focus moved to cognitive stimulation – gentle activities to keep the brain going, such as word games, puzzles, music, and practical activities such as baking or indoor gardening. A Cochrane medical review in 2012 found that 45-minute sessions at least twice a week helped people with mild to moderate dementia. There was some evidence that people were better able to reason, communicate and interact with others, and had a better quality of life. Such activities are now standard in dementia homes and day centres, along with dancing and gentle exercise and singing, all of which Mum loves. And how else would she spend her time?

There are other theories. Penny Garner in Oxfordshire, whose mother had dementia, devised Specal (originally an acronym for specialised early care for Alzheimer’s) to help families and carers communicate with a relative who has dementia. At the heart of this is the photograph album – the concept that people have memories stored like photographs, recording feelings as well as facts, and that when the facts disappear, the feelings remain.

Garner considers dementia a disability and has three golden rules: don’t ask questions that will only cause distress when the person cannot find the answer; listen to the person with dementia and offer them only information that will make them feel better; and do not contradict. Her son-in-law, the psychologist Oliver James, wrote a book about the method, called Contented Dementia, and many of its adherents are enthusiastic. But the Alzheimer’s Society is outright opposed, arguing that not asking questions deprives people of choice and control over their lives.

The society is not enthusiastic about the idea of dementia villages, either. Dominic Carter, its senior policy officer, agrees that people have to be understood, offered activities and encouraged to eat and drink, but thinks it is “a shame if we are willing to accept that the only way to do that is to segregate people and have them in environments that are so specifically focused”.

Instead the society wants to normalise dementia, with a flagship programme to accredit “dementia-friendly communities” – ordinary towns where the baker and hairdresser have been taught how to talk to people with dementia, and where local residents and bus drivers will be better able to see them safely home. So far, it has registered 400 communities, from Minehead to Billericay and beyond. Local Alzheimer’s groups enlist shops, GP practices, libraries, churches, fire, police and social groups, whose members undertake training. There are also activities. Over one week in May, in Tamworth in the west Midlands, there was singing in the shopping centre and community knitting of forget-me-nots to aid the society’s dementia campaign, which includes a call for a £2.4bn government fund to help people with care costs.

People with mild dementia will be safer and happier in a town that has more understanding, although the chances of getting lost in a city like Leeds must still be high. But as the disease progresses, the need for full-time care grows. While we might dream of Grandma sitting in a corner of the family home, watching life going on, being looked after by her children, that’s a fantasy, says Professor June Andrews, former director of Stirling’s Dementia Services Development Centre in Scotland.

“It’s never been families taking care of their own,” she says. “It’s been women. The extent to which it happens is related to the economic value of women.” In countries where women are uneducated and unemployed, they do the caring, she says. “As soon as the daughter or daughter-in-law can get a job, they start importing a foreign domestic worker.” And once those salaries rise out of reach, care homes spring up.

In the UK, there will be a shortage of 30,000 residential dementia places by 2021; the costs remain high and the quality is sometimes questionable. The Care Quality Commission reports that more than a fifth of services either require improvement or are inadequate. Is the Hogeweyk model the answer? It has been controversial since its inception in 1993. Medical experts didn’t like it, while other care home owners feared for their own business model. In the UK, the notion of a dementia village has been dismissed as gimmicky and too expensive – often by experts who have not visited. Although it is run as a not-for-profit, the cost for each resident is £53,000-£59,000 a year, paid for by the government. Local authorities in the UK pay about £30,000 to £40,000 for a residential care home place.

Andrews is sceptical of the Hogeweyk’s “lifestyles” approach but says her own parents – a bus driver and a secretary – would never have been comfortable in a posh care home. “Having something that fits with what somebody is comfortable with is really important,” she admits. But how would you categorise people in the UK, or find the volunteers the Hogeweyk relies on? “The bottom line is, who is going to be able to afford your model if it can only work with an army of volunteers? In the UK, hundreds of care homes are having to shut down because their buildings are not the right quality and they can’t get the right staff.”

But New Zealand and Australia have similar villages, and the first to be modelled directly on the Hogeweyk is likely to open in the UK later this year, in east Kent. Henry Quinn and Dr Phil Brighton, from East Kent Hospitals Foundation NHS Trust, tell me they were profoundly moved when they visited the Hogeweyk in 2015. “What struck me most was when they said, ‘The most important things are the front doors.’ If you have a front door and it’s raining, you can go out and get wet,” Brighton says.

Quinn went up on to the roof of Buckland hospital in Dover and spotted six semi-detached blocks of derelict houses. They got funding from Europe and are on track to open soon.

“It’s a gated community,” Brighton explains. “There will be a boundary fence but not obtrusive or oppressive.” There will be a hub where locals and residents with dementia can go for entertainment, as well as a cafe and a gym. The houses will have five bedrooms each and no locked doors. The team are exploring ideas with the local community, including keeping goats and forging links with a primary school, bringing children in for activities.

If we let them, people with dementia take buses to the end of the line. One man, used to global travel, evaded his carer, travelled to the airport and hopped on a plane to the country where he grew up. People in residential homes used to be restrained, tied to chairs. That doesn’t happen any more. In the dementia-friendly communities the Alzheimer’s Society promotes, technology might allow more wandering. There are already GPS devices, informing relatives of people’s whereabouts – whether they want it or not.

And that is the hardest part: knowing what someone wants. We make decisions for those with dementia in the hope of protecting them. Sometimes, when you hear of a woman, such as a friend’s mother, rocking in her seat, whispering, “Help me, help me”, you have to wonder if we have got it right.

My mum hates locked doors. When she lived in her flat, there wasn’t a day when she didn’t potter to the local shop or get the bus to town. It saddens me to see her wanderings reduced to a corridor and now, even though she is in a safe place with wonderful carers, she is starting to fall; last time I visited, I found her with bruises in another resident’s room, as she frequently is. And for the first time, I did not get the sense that she knew who I was.

For Spiering, caring for people with dementia is all about calculated risk – “accepting frailty and that, in nursing homes, people are going to have falls, and are going to die, and we can’t prevent that. But we can add quality of life. And it’s not by locking them up and not seeing them as human any more.”

My mother is well looked after, by people who see her as human and lovable – but I am disturbed by her constant desire to leave. I want her to be safe, but even more than that, I don’t want her to be unhappy. Most of all, I want her to live the life she wants, in the little time she has left. And it hurts that she can’t tell me – even if she knows – what that is.